Photograph courtesy of Jarrod's Place

Within maybe five seconds, I was obviously in way over my head. I was zipping down a red-clay mountainside trail on a bicycle built for gravel country roads, fighting gravity and losing, dodging young Georgia pines and boulders, trying to keep hold of the handlebars like a whiskey-drunk cowboy on a spurned bull’s back. Which is to say: an awesome, random, terrifying way to spend a Friday afternoon.

But that’s my fault for listening to Frank. (More on Frank in a minute). Very much a “green” mountain biker, as they call novices, I’d recently scored a good deal on an all-carbon Trek on Craigslist, and while studying up on how to correctly ride the thing, YouTube’s algorithm suggested I watch videos from something called a “shuttle-service bike park” northwest of Atlanta, in the wilds between Summerville and Rome. That led to exhilarating, harrowing GoPro videos of what can only be described as a snowless ski slope for mountain bikes: almost no pedaling required, all downhill, just wind, twists, dips, speed, embankments, and adrenalized spurts of airborne acrobatics between the trailhead and the safe, flat base below. All of it was situated in gorgeous, rugged woodlands, the green ridges lumping off forever, the dirt the color of rare meat.

That’s in Georgia? I thought, pointing a Tropicalia at the TV one weekend. And right up the road?

Photograph by Josh Green

Photograph by Josh Green

Indeed. The complex is called Jarrod’s Place Bike Park, the brainchild of two thrill-seeking buddies with disparate dreams for the same industry. It celebrated its first anniversary May 7. And it’s already established itself—without really trying to—as an international destination, an anomaly in a burgeoning sport, and a boon for one of Georgia’s poorest counties.

Within a few weeks of the YouTube epiphany, with a little (woefully insufficient) riding under my belt, I headed north after a tough, stressful workweek to brave the mountain, learn how the business came to be, and figure out who this Jarrod guy is.

• • •

Before his eponymous bike park opened, before a wild run with standup comedy that landed him on Comedy Central and in a friendship with Bill Burr, Jarrod Harris was a poor, mischievous kid in Powder Springs. As he recalls, he all but raised himself. But something about riding his bike lifted his spirits. He discovered BMX racing, and during stints when he was homeless, he’d climb into the announcer’s tower at a track in Powder Springs and sleep.

“We used to just ride and get in trouble,” Harris, now 47, says with a laugh.

The late John Kovachi, a legendary wheel-builder in the BMX world, took Harris under his wing—and then to national competitions when the young rider was good enough to make a traveling team, beginning at age 13. A couple of years later, Harris discovered his knack for sitting down at a drafting table and designing tracks, winning a nationwide contest put on by the National Bicycle League in the early 1990s. His gut said large-scale bike parks would exist in the future, but they didn’t start popping up until the early 2000s, mostly at ski slopes in western U.S. states eager to draw visitors back during summer months.

Laidback and witty, with a twisted sense of humor, Harris found that his BMX travels served him well in another venture tethered to the open road: stand-up comedy. (Fellow Southern stand-up Stephen Colbert liked his stuff, he says, and initially encouraged him to regularly take the stage.) Harris took a leap of faith in 2009 and moved to Los Angeles, where Burr and other top-flight comics, he says, helped show him the ropes. He cracked up George Lopez on his late-night talk show in 2011 and created a web series, Action Figure Therapy, that was an early viral YouTube hit. On the cusp of landing an FX show, Harris instead hit a roadblock, which for legal reasons he can only describe as, “the harsh end of a bad deal, where I got a lot of my intellectual property stolen from me—legally.” On the bright side, he did meet and marry native Georgian and fellow comedian Lace Larrabee, who runs women-only comedy courses at the Punchline and was a semifinalist on last season’s America’s Got Talent, getting interrupted by Sofía Vergara and hailed as hilarious by Howie Mandel.

Burned by Tinseltown’s make-it-or-bust rat race, Harris declared himself on comedy hiatus in 2015 and used his earnings to buy heavy equipment and a bucolic piece of property in Jasper. There, in his backyard, he created trails with monstrously big jumps, started a power-washing company as a day job, and again found solace in riding his bike. “I just stayed in the woods,” he says. “Kind of bitter and angry.”

Word got out, and riders from around the Southeast started asking to come ride at “Jarrod’s place.” After making them film themselves for hilariously naïve “video waivers,” absolving Harris of all culpability should they get injured or die, he welcomed anyone with enough skill to ride in exchange for $20 donations or manual labor—digging up dirt for more jumps.

Among those visitors was Josh Cohan, 32, another Cobb County native.

With tat sleeves that belie his background as a former Chipotle regional director and real estate wholesaler, Cohan’s early riding experience was in motocross, but like many in that sport, he’d turned to mountain biking to keep fit. Cohan’s dream was to open a bike shop, but he found the metro Atlanta market to be saturated with too many good ones already. He and Harris discussed melding their visions to create a legit, paid bike park with shuttle-truck service to the top of a mountain—a first for Georgia—and a full-service bike shop at the bottom for upgrading or fixing bikes. In Cohan, the former standup saw the antithesis of himself: a guy with corporate experience, skilled at managing people.

Harris and Cohan piled their life savings, shirked potential investors, and set off to find the right location. A couple of deals fell through. But deep in the pandemic malaise of 2020, the duo took a ride to Summerville, parked the car at a 230-acre former tree farm, and immediately said to each other: “Okay, this is the place.”

• • •

Located about 80 miles from Midtown, off the same Interstate 75 exit as Barnsley Gardens and along a series of twisty asphalt roads, Jarrod’s Place is nearly the size of Chastain Park, only with a dramatic 900 feet of elevation change. Building its initial phase from scratch took Harris, Cohan, and a team of a half-dozen contracted, full-time workers about 14 months, cleaving through brush Cohan describes as “crazy dense.” A marsh across the road and plentiful boulders meant the mountainside was dotted with rattlesnakes and copperheads—not to mention wild boar and, according to scat and tracks found one day, at least one bear. The park’s noise, says Harris, has since shooed the wildlife elsewhere.

Photograph by Josh Green

Photograph by Josh Green

Photograph by Josh Green

At the mountain’s base is a 1,500-square-foot building, colloquially called “Headquarters,” with the pro bike shop inside, a fenced dog park outside, a bike wash, and 24-hour showers and bathrooms. Just up the hill, along a one-mile road that now circles up the mountain and back, are forty campsites. Those welcome riding enthusiasts with tents and campers—often on a tour of bike parks around the Southeast, such as North Carolina’s Sugar Mountain and Tennessee’s Windrock Park—all week, year round. Unlike most bike parks in the West and Southeast that double as ski slopes, Jarrod’s Place doesn’t have an off-season for biking, given Georgia’s temperate winters; combined with the unique red-clay terrain, technical lines, and according to reviews, well-designed, flowing trail systems, that fair-weather accessibility has already made the bike park a surprise winter hit for riders near and far. Visitors have come from the Dakotas, Montana, California, Canada, even Europe, and especially from Florida, as it’s the nearest true mountainside park to the Sunshine State. Race weekends have sold out for competitors, with as many as 600 riders and spectators on site at once.

“Sometimes it’s a little weird,” Harris concedes, “because you’re like, There are more out-of-state plates here than Georgia plates.”

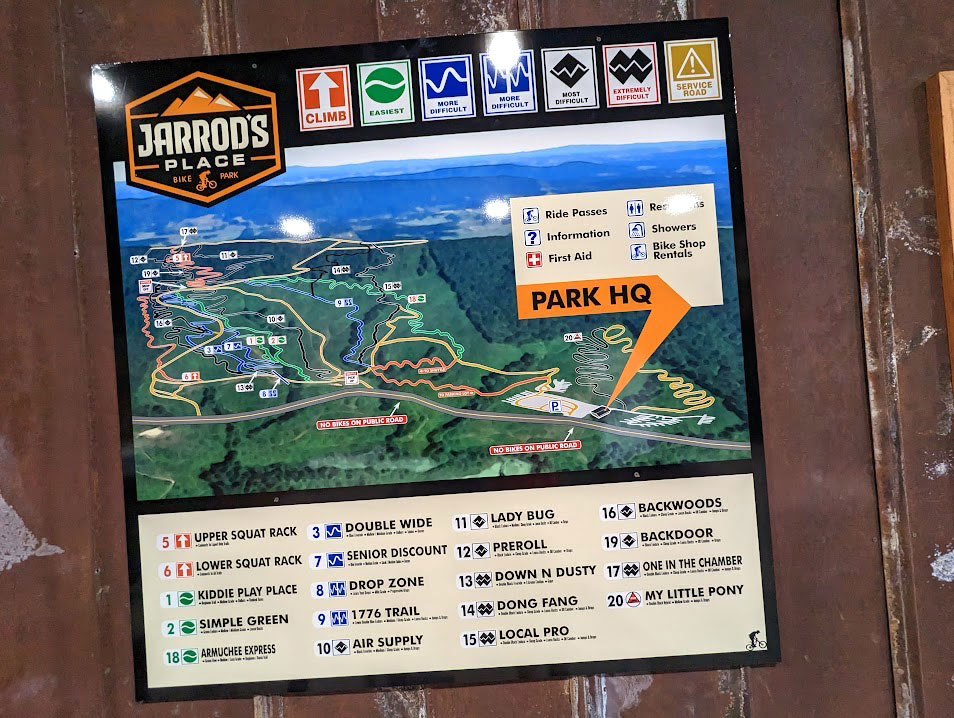

Harris is currently building the park’s 20th trail, with plans for more beginner-grade stuff on the horizon later this year. Trails range from a green-level kid zone to crazy-steep, double-black-diamond madness. (Pro tips from an amateur: This is no place, at least not yet, for that dusty Walmart Huffy in your garage. Strong, fresh brakes are your friend. And if your bike doesn’t have an automatic dropper-post, be sure to put your seat at its lowest setting beforehand, as spoken from painful experience.) At busy times, the park runs three shuttle trucks with long racks for bikes behind, meaning your ride is usually waiting at the bottom by the time you arrive. Cohan estimates that, as is, only about 1/8th of the acreage has been tapped into for trails, roads, and infrastructure, such as new channels for drainage. Harris guesses the outlay so far has been between $1.5 and $2 million.

Photograph by Josh Green

Photograph by Josh Green

Photograph by Josh Green

As for pricing, Jarrod’s Place memberships start at $50 for a full day of riding with shuttles (up to eight hours on weekends), with six-month passes costing $450 for adults. Asked if patronage has met his expectations so far, Harris seems a bit befuddled. “There’s no pamphlet to follow for this—it’s just a giant experiment,” he says. “I never try to put a number on it, but we seem to have had a very good first year, and we seem to be growing steadily every month, as more people are finding out about it.”

One positive aspect that nobody anticipated was the economic boost Jarrod’s Place has brought, at least anecdotally, to Chattooga County, where per capita income for a population of less than 25,000 is estimated at just $19,500.

“Now our neighbors have Airbnb, and they’re able to make money,” says Cohan. “And our town, Summerville, is getting tons of revenue from this traffic of people going to the restaurants, the gas stations. It’s really cool to see. When we go into town now, everyone knows who we are, because of the mountain bikes, which were nonexistent before. People thought we were crazy, like, ‘You’re going to ride not up that [mountain], but down it?’”

• • •

So back to Frank. On my maiden voyage up the mountain, a friendly construction industry recruiter from Cartersville named Frank convinced me to try a blue-grade trail called “Double Wide” for my first run. Don’t do that. If it’s your first time at a downhill bike park, listen to park management, and slowly ease into the experience. If you’re green, start on green. Because the threat of Wile E. Coyote-style physical calamity is real.

For the next two hours, though, I stuck with the easiest green route, Armuchee Express, which is still a long and wild ride. After Frank found a multitool to mercifully lower my seat, it became truly fun.

Photograph by Josh Green

About four runs in, I began to feel confident, pushing harder, breaking a sweat, and finding that euphoric adrenaline rush of a clean fast run on a ski slope. We zipped across little bridges over babbling streams, up muddy embankments, and through dense woods. The two dozen riders on a post-thunderstorm Friday included teenagers, high-flying pros, grizzled older riders, men and women, and several people recounting their experiences in Spanish. Each shuttle ride back to the top engendered a new sort of camaraderie, a sense of adventure, and excited chatter about what just happened and who nearly wiped out (or who did, in the case of a woman who sprained her ankle). The workaday stresses of city life seemed a million miles away.

“Overall, I think we hit a home run, because we’re not far from Atlanta and we’ve got this little slice of heaven,” Harris says, reflecting on the bike park’s first year. “Our next goal is to be ambassadors for the sport and really get people into it. Because honestly, riding bikes, it saved my life.”

Photograph by Josh Green