Photograph by by Jason Thrasher

Johnny Jenkins was having heated words with Little Richard. They were the kind of words that can get you banned from a limo ride, which is exactly what happened. That’s how Jenkins, the southpaw guitarist from Macon who discovered Otis Redding and inspired Jimi Hendrix, wound up in a yellow cab with poet and music gadabout John Griffin, instead of in a limo with the Real King of Rock ‘n’ Roll, that rainy night in September 1996, heading to celebrate the opening of the Georgia Music Hall of Fame.

“He cussed Little Richard all the way there,” says Griffin, recalling their ride from the pre-gala reception to the new $6.5 million facility on Macon’s Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. Griffin, in his tux, blended in like Zelig with the crowd of red-carpet celebrities jostling under a bobbing forest of umbrellas.

“I had no business on that red carpet with R.E.M. and the B-52s and all of them, and I kept asking myself, ‘What the hell am I doing here?’ But I had nowhere to run, nowhere to hide, just went with the forward momentum,” says Griffin, who has a knack for securing backstage passes. “We got to the front, and there was a man I recognized. He shook my hand and said, ‘Hi, I’m Zell Miller.’”

The governor himself. The man who created the Georgia Music Hall of Fame.

He was Georgia’s lieutenant governor in 1979, when he initiated the Hall, and Ray Charles and Bill Lowery were the first inductees. This was a legacy project, something he was immensely proud of. But Miller—who served Georgia as a state legislator, then lieutenant governor, then governor, then U.S. senator—outlived his legacy. When he died in 2018, the Hall had been dead for eight years. Or it might have been three years. It’s confusing, like so many other things concerning the Georgia Music Hall of Fame and its weird history.

• • •

What is a hall of fame? Is it the building that contains artifacts, plaques, and statues honoring famous people, or is it the people themselves? Is it a physical place, or a transcendent honor? During its wobbly lifespan from 1996 to 2011, the Georgia Music Hall of Fame was all those things, until it wasn’t anything.

It began as an honor—recipients accepted their awards (called the “Georgy Awards”) each year at a fancy shindig in Atlanta, the culmination of a statewide celebration called Georgia Music Week (which eventually became Georgia Music Festival). Every year, a committee of legislators and music industry people selected the inductees. The plan had always been to find a permanent place for a museum. The initial thought that floated around was to put something in the World Congress Center in Atlanta. But in 1989, the state legislature selected Macon (while also turning thumbs down on giving Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” the distinction of being the state’s official rock ‘n’ roll song).

“No other site in Georgia ever seriously crossed my mind,” Miller said at the time, adding artists like Little Richard, Otis Redding, and the Allman Brothers Band, along with Phil Walden and Capricorn Records, put the city “at the forefront of musical history in Georgia.”

Work began on finding a site, and Miller put a team together. In 1991, he formed the Georgia Music Hall of Fame Authority to oversee the design, construction, and operation of the facility. One of his nine appointees was Bobbie Bailey, an influential businesswoman and president of a nonprofit called Friends of Georgia Music Festival (later to lose the “Festival” part of the name).

In hindsight, Bailey was an unusual choice for this particular group—she never wanted the Hall of Fame in Macon. Years later, when the museum was in its death throes, she said, “The Hall of Fame needs to be in Atlanta. It’s in the wrong place. It’s been in the wrong place since the beginning.”

Nonetheless, the opening celebration took place on Saturday, September 21, 1996, under a deluge of weather. The fog was so thick, and it rained so hard, that Kenny Rogers’s plane was unable to land. Jami Gaudet, the Hall’s public relations director at the time, remembers Little Richard running along the soggy red carpet, greeting fans. “It was the craziest night, 1,200 people crammed into the building like sardines,” she says. “And it was fabulous.”

The next day, Zell Miller cut the ribbon to officially open the museum. So began a long slide into oblivion. Ambitious projections of more than 200,000 annual visitors were never realized—the high was closer to 25,000.

As Miller noted early on, Macon is near the geographic center of the state. “It is the magnet which can draw the hundreds of thousands of motorists traveling to and from Florida on Interstate 75,” he said. “And it is only an hour and a half away from metropolitan Atlanta—a traveling time which will be considerably less when we get one of those bullet trains connecting the two cities in the 21st century just ahead.”

Unfortunately, the museum was not built along I-75, but off I-16, one of the least traveled interstates in the country. Also . . . bullet trains? Well, it was 1989, and Miller can be forgiven his moment of progressive-minded hubris. Either way, the museum didn’t attract many visitors on their way to or from Florida.

But for those who did stop in, the museum was a first-class experience. The large exhibition space on the first floor was called Tune Town, and it was broken up into sections dedicated to different genres, with artifacts of all kinds (photos, instruments, records, costumes, and equipment), much of it on loan from Hall of Famers.

Photograph courtesy of the Georgia Music Hall of Fame

“It was such a special place to work,” says Gaudet, now a freelance writer and public information officer for the Macon–Bibb County Transit Authority. “Everyone employed there cared deeply about making it a success. But it was difficult. I know that the Atlanta folks were rankled from the start.”

She means Friends of Georgia Music, the organization that Bailey led. Friends was created in 1979, with help from the governor’s office, and incorporated as a nonprofit, so that it could work as a contractor for the Department of Community Affairs (the government agency that oversaw halls of fame at that time, a task since turned over to the Georgia Department of Economic Development) and receive state funding. Music publishing mogul Bill Lowery was its first chairperson. In 1989, Bailey took over and led the organization for 25 years, producing the awards show and working with the Georgia Senate Music Committee to pick inductees. Perhaps more accurately, the committee was working for Bailey and Friends.

“Dr. Bobbie Bailey was the leader of the pack,” says Jeff Mullis of Chickamauga, who retired last year after 22 years in the state Senate. For much of that time, he chaired some form of the music committee. “There was nobody who could fill her shoes.”

• • •

For many years, the relationship between the Georgia Music Hall of Fame Authority and the Friends of Georgia Music (or the state Senate Music Committee that it seemed to control) was toxic.

Basically, one group was created to maintain and operate a facility in Macon, while the other group had possession of the keys. Lisa Love, the last executive director of the Georgia Music Hall of Fame, says the Authority had no influence over who was inducted into its Hall of Fame (a circumstance that always seemed to surprise new Authority members after they joined). And the Authority had nothing to do with the annual awards gala (usually at the Georgia World Congress Center). The museum’s staff had to buy tickets to the event like everyone else, and the Authority purchased an ad in the printed program. The show was broadcast on Georgia public television and lost money every year.

State government supported both entities for a while, but then stopped. That made Bobbie Bailey more important than ever.

“Once the state pulled its funding from the Georgia Music Hall of Fame awards event, it was Dr. Bobbie Bailey all those years who underwrote the loss,” says Michele Caplinger, executive director of the Atlanta Chapter of the Recording Academy (producer of the Grammy Awards), who worked closely with Bailey as one of the Friends.

Bailey was a driven, strong-willed, and multiskilled entrepreneur, a self-made millionaire, and a woman ahead of her time. She started and sold companies and generously shared her wealth, supporting the causes that mattered most to her, such as music education and athletics. She established music scholarships at Georgia State and Kennesaw State Universities, and the endowment for the Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center at Kennesaw State. She also gifted the school with 44 Steinway pianos, established women’s athletic scholarships, and endowed the Bobbie Bailey Athletic Complex. KSU gave her an honorary doctorate.

Photograph by by Jason Thrasher

Photograph by by Jason Thrasher

Caplinger says Bailey was “a dear friend, and a powerhouse of a leader, philanthropist, and wondrous supporter of the arts. She was a self-made woman who broke every barrier back when women were not typically invited in or welcomed in business. It’s remarkable what all she accomplished. Her passion and generosity for music makers was unparalleled.”

So was her determination. The decades-old power struggle between the Authority and Friends was never resolved. But it probably reached its ugliest peak as the museum in Macon was nearing completion. In 1996, Friends applied for a trademark for the names “Georgia Music Hall of Fame” and “Georgy”—a curious maneuver by Bailey’s team, since she was a member of the Georgia Hall of Fame Authority, ostensibly charged with protecting the Hall’s interests.

Friends got the trademark in 1997, and soon after, the Department of Community Affairs asked Georgia Attorney General Thurbert Baker to offer his opinion on the legality of Bailey’s organization owning the trademarks. He concluded that the Authority owned the trademarks, adding, “The Georgia Constitution may prohibit the Georgia Music Hall of Fame Authority from delegating the exclusive right to select inductees into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame to any private entity, including The Friends of Georgia Music.”

The opinion was toothless, however, because neither the state nor the Authority sought to enforce the ruling. The Friends and the Senate committee continued to choose inductees, and the rift grew into a black hole that eventually sucked everything into it.

• • •

Between 1979 and 2015, 163 people were inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame. As with any other hall of fame, there are the people who obviously belong (Little Richard, James Brown, Otis Redding, the Allmans, Brenda Lee, Chet Atkins) and some puzzling selections (comedian Jeff Foxworthy, television personality Monica Pearson, and the Florida-born and -based band Lynyrd Skynyrd).

For many years, the committee gave out four Georgy Awards: performer, nonperformer, posthumous, and the Mary Tallent Pioneer Award. But the committee ditched that process in later years and started to induct more people each go-around. In some ways, the award became more like a Grammy and less like a hall of fame honor, as some inductees were young and relatively early in their careers, such as Chris “Ludacris” Bridges (who was 31 when he was inducted in 2008) and the country bands Sugarland (2012) and Lady Antebellum (2014). Those inductions were less about career longevity or impact, and more about current popularity. The idea was that their presence (or performance) would help sell tickets to the event, Bailey explained following Sugarland’s induction.

Photograph by Getty/Rick Diamond

There are also some unexplainable omissions, including new wave bands Pylon and the Swimming Pool Q’s; Atlanta bandleader, musician, and performance artist Col. Bruce Hampton; Rutha Harris and Bernice Johnson Reagon of Albany, members of the Freedom Singers, who gave the civil rights movement a powerful rhythmic voice; and cowboy singer and songwriter Ray Whitley, who cowrote Gene Autry’s hit “Back in the Saddle Again”—not to be confused with the other Ray Whitley from Georgia, the 1960s composer who cowrote the beach-music classic “Be Young, Be Foolish, Be Happy” and was inducted in 1991.

Zell Miller had been a stalwart protector of the Hall’s budget for years, but his term as governor ended in 1999, and state support began to wane after that. “The museum’s annual operating costs and its dependence on public funding made it extremely vulnerable after the economic downturn of 2008, especially as the political tide was turning in Georgia,” says Love, who is now executive director of the Macon-based Georgia Music Foundation, a nonprofit focused on music education, preservation, heritage, and outreach. “Priorities shift with each administration. That’s just the way it works.” Under the administration of Governor Sonny Perdue, state government support finally dwindled down to nothing.

In the fall of 2010, the state put out a request for proposals to either move the Hall out of Macon or identify a sustainable plan to operate the museum. Several cities, including Athens, sent in proposals. But the timeline and expectations were unrealistic, says Love, and in May 2011 the Georgia Music Hall of Fame Authority voted 4–3 to close the facility. The artifacts were packed up. Some were sent back to the families who had loaned them, others were shipped off to the special-collection libraries at Georgia State University and the University of West Georgia, but most of them went to the University of Georgia in Athens. In 2012, the state sold the museum’s building for $186,000 to Mercer University, which used it to expand its medical school.

The Georgia Music Hall of Fame in Macon was dead. But the Georgia Music Hall of Fame Awards continued on life support. Inductions continued for several years. On July 25, 2015, Bailey died at age 87. Two months later, the awards show took place at the Georgia World Congress Center. The inductees included Gregg Allman (amazingly, his third induction, this time as a songwriter, having previously been honored as both a solo artist and an Allman Brother—Mullis is a big, big fan); Sam Moore (of Sam & Dave); and John and Jane Barbe, who received the Pioneer Award. There have been no inductions since. After 37 awards shows, the whole thing died with Bobbie Bailey, who “always made sure we had the money to take care of things,” according to Mullis. “She was so dedicated to whatever she took charge of, and when she passed away, we didn’t have anyone to fill her shoes. We’re still waiting on someone to save us from ourselves.”

So far, there have been talkers but no takers.

Photograph by by Jason Thrasher

In 2020, a nonprofit called Georgia Music Accord announced it was bringing a regional Grammy museum to Atlanta. The state and Fulton County underwrote a $500,000 feasibility study. Caplinger, who serves on the organization’s board, said recently that the museum would include a Georgia Music Hall of Fame wing, adding, “Once that is launched, we felt it would be a perfect time to resurrect a Georgia Music Hall of Fame Awards.”

But according to Georgia Music Accord founder and CEO Brad Olecki, there isn’t a Grammy museum project. “We’re not building a Grammy museum,” Olecki says. “And to be clear, we’re not building a Georgia Music Hall of Fame.”

• • •

David Barbe wants to know what will happen first: the creation of the Georgia Music Office, or the Atlanta Hawks winning an NBA championship. “I’ve been hearing about both for a long time,” quips Barbe, a musician, recording engineer and producer, and director of the Music Business Certificate Program at the University of Georgia. (Barbe’s parents were part of the last induction class in 2015.)

In 2022, Mullis cochaired something called the Joint Music Heritage Study Committee, made up of legislators and people from the music industry. They suggested creation of a dedicated Georgia Music Office, and tax incentives on par with those currently offered by the Georgia Film Office. But some version of that legislation has appeared almost every recent year without passing. It happened again this year, and once again, the bill failed.

Barbe thinks that creating a state music office might provide the clearest path to reviving the Georgia Music Hall of Fame.

“Personally, I’d really like to see this thing happen, and I’m willing to be Switzerland, because I’m a neutral party—I don’t really have a dog in the fight,” says Barbe. “But I love music, I love music history, and I’d like to communicate with all of the interested parties to see what we can do.” Barbe is on the board of Georgia Music Partners, a trade association that lobbies on behalf of the music industry, and is friendly with the Atlanta Grammy people (his father cofounded the chapter). He also has a long and positive working relationship with Lisa Love, and he was part of the last Georgia Music Hall of Fame Authority.

“If memory serves, I was the last holdout that voted to close the museum, which was brutal,” Barbe says. “I mean, this was a tough pill to swallow—my parents are in the Hall of Fame. The math just wasn’t good. It was an impossible situation.”

But he believes now what he believed back then. “Georgia needs a music hall of fame,” he says. “And I’d like to do whatever I can to help make that happen.”

When cities around the state responded to a Hall of Fame RFP (the last-ditch effort in 2010 to preserve a hall), Barbe was most impressed with his home city’s proposal, which described a hub-and-spoke kind of model, with Athens serving as a headquarters and exhibitions rotating to cities across the state.

“I liked that it wasn’t dependent on foot traffic to a building that costs some municipality a lot of money,” he says. “And it could be housed anywhere. That seemed cool to me because it was the lowest-cost solution and would affect the most people.”

The Athens proposal, voted down like all the others, included a plan to preserve the collection at the University of Georgia library. Of course, that’s where most of it wound up. And now, Barbe says, “They’ve got the right guy taking care of it.”

That would be Ryan Lewis, the Georgia music exhibit coordinator at UGA’s Special Collections Libraries, who thinks of himself as the Indiana Jones of music.

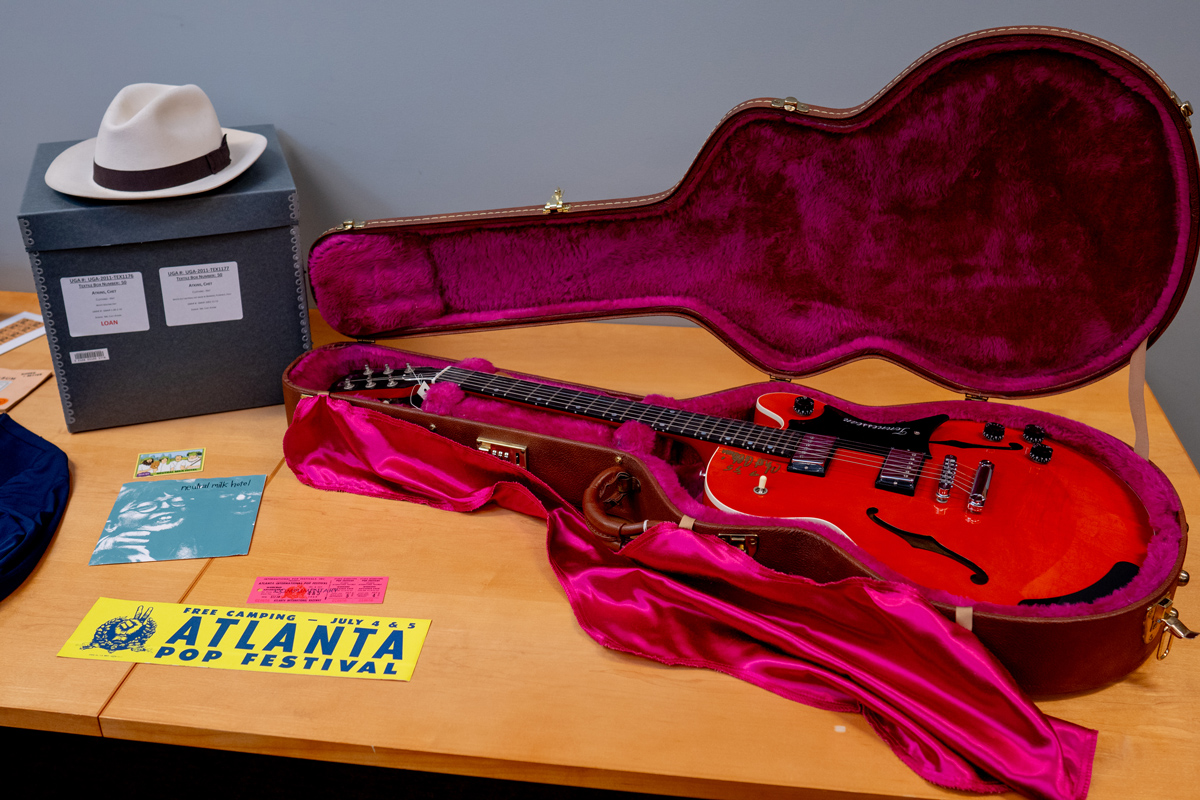

“I’m a rock ‘n’ roll treasure hunter surrounded by a lot of really cool stuff,” says Lewis, sitting at the head of a conference room table laden with his latest discoveries. There’s a cape worn by James Brown, and one of his shirts, the dye faded on the collar by Soul Brother No. 1’s long-ago sweat. And there’s a pair of his shoes, scuffed on the bottom. There are records, concert posters, and a set list from the Atlanta International Pop Festival. Below this floor is a two-story climate-controlled warehouse filled with more musical treasures, including items from the Georgia Music Hall of Fame.

Visitors to the library can view (under supervision) an article of James Brown’s clothing with the same ease with which they might check out a reference book to study. Registering with the library takes about a minute, and then it’s another 15 minutes or so for a library employee to fetch the artifact of choice. Unless it’s a musical instrument—say, a guitar that belonged to Johnny Jenkins. “Sometimes we need 24-hour notice for those, because they’re stored somewhere else,” Lewis says. “The point is, this stuff is available, and we love sharing it with visitors.”

There are exhibits of music memorabilia in the library building now, and soon Lewis will be pulling some artifacts together and arranging them for an extensive display at the new $126 million Classic Center Arena, which is taking shape in downtown Athens and set to open this year.

“The events there will generate a lot of foot traffic,” says Paul Cramer, president and CEO of The Classic Center, which already hosts 500 events a year as a convention center and performing arts venue. “We’ll be able to share Georgia’s music heritage with many thousands of people,” he says.

The music history exhibitions will be open to the public when there are not scheduled events. “I was intrigued by the idea of this collection being here in Athens, and the opportunity to make it available to more people,” Cramer says. “But the idea really took root when the museum in Macon closed all those years ago.”

For people in Macon, the loss can still be heavy.

“I can’t tell you how hard it is to see the building and know that such an injustice was done to Macon’s and Georgia’s music industry,” Gaudet says. “Mercer got the bargain of the century.”

For Chuck Leavell (Georgia Music Hall of Fame class of 2004), the loss is personal. Leavell was 18 when he relocated to Macon from Alabama to play with the Capricorn Records studio band, and he then joined the Allman Brothers the year after the death of guitarist Duane Allman in 1971. Since 1982, he has been the pianist and organist for the Rolling Stones.

“It just breaks my heart, the way everything went down,” says Leavell. “My wife, Rose Lane, was part of the Hall of Fame Authority. She was in the minority of folks who voted to keep the museum in Macon. So it really hurt when it closed, because she supported it, she believed in it. When you think of all the great music that has come out of this state, it’s just mind-boggling. It’s crazy that Georgia doesn’t have a music hall of fame.”

This article appears in our May 2024 issue.