This story is part of Atlanta magazine’s Streets Issue—a block-by-block exploration of our city and the stories it tells. Find the entire package here.

Edwin Wiley Grove had the hiccups—chronically.

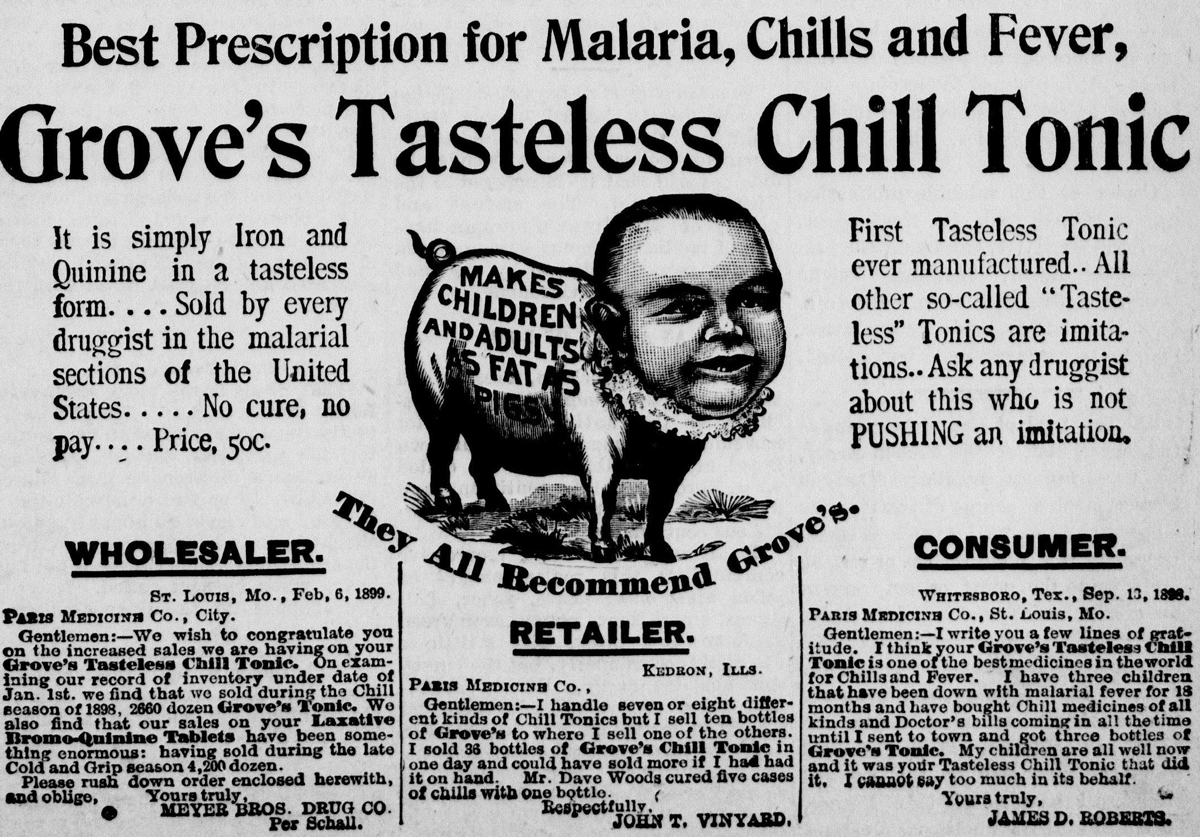

Coming after Grove had first found success but before his career reached its apex, the hiccups played an important role in the trajectory of this early 20th century multimillionaire. Born in Tennessee in 1850, Grove lost a wife and a child to malaria, inspiring him to create a “tasteless” treatment for the disease that contained quinine but—and this was the selling point—sought to counteract quinine’s bitter flavor. It was in fact not tasteless but sweetened and lemon-flavored, and reputedly disgusting—not quite a thing you could splash into a vodka tonic. (Besides, Grove was a prohibitionist.) By 1890, Grove’s tonic was apparently selling more bottles than Coca-Cola, in spite—or because?—of a chimeric ad campaign depicting the head of a baby affixed to the body of a pig: GROVE’S TASTELESS CHILL TONIC, it says. MAKES CHILDREN AND ADULTS AS FAT AS PIGS. Bottoms up.

“As a poor man and a poor boy, I conceived the idea that whoever could produce a tasteless chill tonic, his fortune was made,” Grove recalled. After realizing that fortune, he moved his manufacturing plant to St. Louis, where the smoke and smog of the factory district led him to develop the hiccups. That pushed him toward Asheville, where Grove is today remembered as a real estate developer, notably of the Grove Park Inn, a luxurious mountain retreat that’s hosted presidents from FDR to Barack Obama (and is reportedly where the Supreme Court would be sent in the event of an attack on Washington, D.C.); the Grove Arcade; the Battery Park Hotel; and Grovemont on Swannanoa, a planned community whose plans were derailed by Grove’s death, in 1927, and the subsequent financial crash.

Asheville’s Grove Park, of course, will not be the one most familiar to Atlantans: E.W. Grove was also responsible for the development of our own Grove Park, previously called Fortified Hills and, for a while, West Atlanta Park. A 1913 ad in the Atlanta Constitution: “Have you been out yet? Did you notice the excellent car service out there? Did you look at the good roads on the way out? Did you select YOUR future Home?” Elsewhere in Atlanta, Grove was also behind the development of Atkins Park, though the neighborhood that today bears his name actually bears more than that: Grove Park’s Gertrude Place, Evelyn Place, and Edwin Place? They’re all Grove family members, as Margaret, Matilda, Hortense, and others in the area are also thought to be. Other Grove relatives had a less benign impact on the city: Grove’s son-in-law was Fred Loring Seely, who first worked for Grove’s pharmaceutical interests before founding—with Grove’s backing—the Atlanta Georgian, a newspaper remembered today for helping incite the white rioters who, in 1906, killed dozens of Black Atlantans.

This article appears in our August 2022 issue.